Back to all articles

2019 Harvest in the Demonstration Garden

On the last warm day of fall, a small reservoir of pee glistened golden in the sun at the Rich Earth Institute. Tatiana, Bradley, and I arrived to put the garden to bed for the winter just as the pee-truck returned from its rounds. There are many kinds of final harvests that mark the change of season; many unusual practices that slowly become seasonal, routine.

Arthur and Mike had just completed the last collection of urine before winter fully set in and the home storage barrels froze solid. In the garden, we were busy at work, pulling vegetables from the earth before the first frost. Arthur and Mike began to pump pee from the truck into our storage tanks and then into the pasteurizer. As we clipped the last of the kale, the subtle scent of urine pervaded the air. We dug up carrots to the tune of the urine vacuum pump’s gentle humming.

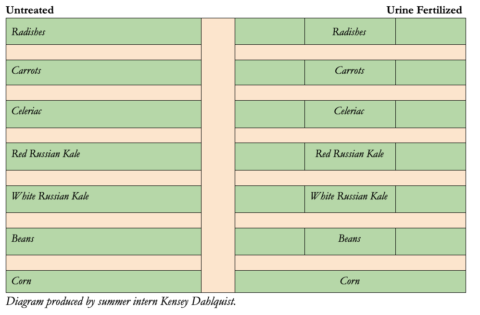

Last spring, we had populated our demonstration garden with Cherry Belle radishes, Watermelon radishes, Red Core Chantenay carrots, Brillante celeriac, Red Russian kale, White Russian kale, Black Valentine beans, and Red Kernel popcorn. Each plant received a bespoke amount of urine to suit their nitrogen needs. We experimented with different concentrations of urine for each plant, to determine the optimum level of dilution to transfer nitrogen from the urine to the plant. For larger-scale farms, we’re actually working to concentrate the urine to reduce the time and energy required to fertilize hay fields. But at the garden scale, diluting the pee with a little water may help the nutrients settle into the soil and ease plant uptake. For each row, we tested three different levels of urine dilution, as compared with no urine fertilization at all.

Each human body produces ten pounds of nitrogen and one pound of phosphorous every year. Rather than flushing valuable nutrients a hundred miles down the Connecticut River—into the Long Island sound, where nitrogen and phosphorous become harmful algal blooms, pharmaceuticals disorient fish, and hormones morph amphibian bodies—in our garden, other nutrient afterlives are possible.

All summer long, Rich Earth staff and interns carefully tended the garden. From within, the garden feels like any other. It’s easy to slip into rote motions of clipping, mulching, watering, weeding. But on days like today, we are reminded of our garden’s uniqueness. Kneeling in the urine garden, I am suddenly aware of being waist deep in plants proudly waving the commingled nitrogen of untold strangers in the wind.

Along with Rich Earth Research Associate Tatiana Schreiber, our interns–Morgan Martinez, Benson Colella, Katie Weitzel, Kensey Dahlquist, and Caitlin Perry—carefully observed the health of each plant, noting color, texture, and size. Each vegetable was then harvested, weighed, and measured.

From this first season of testing, we began to discover the ideal dilution level for each particular species. Our radishes seemed to do best with six parts water to one part urine, while carrots and kale preferred 3:1. The kale received repeat applications of the urine fertilizer. The urine-fertilized celeriac were clearly larger, but an optimal dilution level remains to be found. We found that the corn did best with un-concentrated urine—the average weight per urine-fertilized ear was more than double the weight of the untreated corn. Most crops are happy somewhere between 3:1 and 6:1; we will continue to explore the best brew in the coming years. Next year, we might try planting some perennials—such as asparagus, rhubarb, and blueberries—to study the long term effects of urine as fertilizer.

By the end of the season, our office was overflowing with vegetables. We donated over 300 pounds of produce to Edible Brattleboro. We brought home bounties to cook into pesto, pea soup, and peanut-carrot stew. We shared urine-fertilized vegetables with neighbors, fed them to our families, brought them to our potlucks.

But the measurable results from our study are complicated. We began to notice that vegetable variations are also entangled with each plant’s position in relation to the sun, soil slopes, and pollinator pathways.

A garden is not a petri-dish. Our “control groups” grew out of control. Gardens are complex ecosystems, inseparable from the wider world in which they exist, and not comprised of isolatable bits. Rather than a strict experiment, our garden explorations were more of an observational study. Researchers are always implicated in the subjects they study and this was no different, as we noted the influence of our pee and curiosity on the plants.

As I brush aside soil to lift the carrot from the ground, shards of glass glint in the sun. In its past life, our garden plot was part of the Windham County Landfill. From 1970 to 1995, these 30 acres were a sacrifice zone, accepting the region’s waste and stowing it away. The landfill has since been capped with a layer of clay, a plastic liner, a layer of soil and grass, and, eventually, a 16,000-module solar array. A methane digester slowly consumes the landfill’s emissions and flares a ghostly flame. We are gardening on storied land, above the afterlives of Brattleboro’s waste. Everything about our garden site reminds us that there is no such place as “away.”

Gardening with complicated landscapes—with medicated bodies and industrial zones—requires learning to stay with the trouble that these coexistences carry. “Staying with the trouble,” as Donna Haraway writes, “requires learning to be truly present not as a vanishing pivot between awful or edenic pasts and apocalyptic or salvific futures, but as mortal critters entwined in myriad unfinished configurations of places, times, matters, meanings.” Gardening with human waste involves learning about these tangled connections, following their effects in the thick present.

Do you have a relationship with urine-fertilized plants? Thoughts on dilution levels and the desires of specific vegetables for different proportions of pee? Let us know what you’ve noticed! Email your observations to or comment below.